There are lots of reasons that aging is associated with a decline in health, but the deterioration of the immune system is a significant one. After all, it’s the immune system that allows us to fight off disease and heal from injury, and when it does go wrong, it’s the source of much of the inflammation that contributes to chronic illness. That’s why new research into the potential regeneration of the thymus is so exciting (https://longevity.technology/news/could-regenerating-the-thymus-boost-human-longevity/).

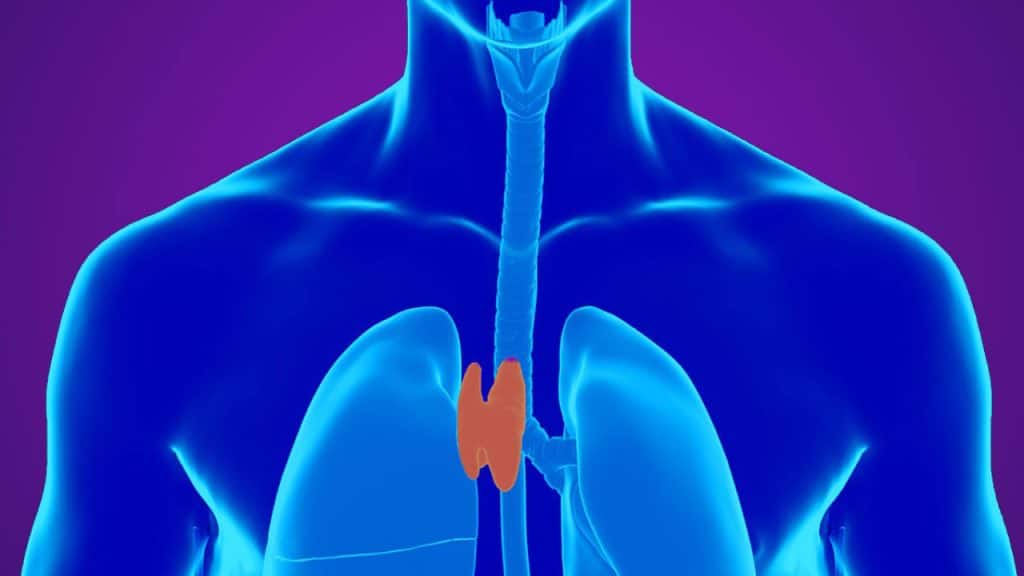

The thymus is an organ in the immune system. It’s small but complex, and we’re still a long way from fully understanding its function and mechanisms. We do know that it is home to immature T cells that will eventually be released into the body to battle infection. It’s also vital to ensuring that only invading pathogens are attacked. It stops the immune system from turning on itself and treating your own body as a threat.

That’s important because in autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes, the immune system tries to destroy healthy parts of the body. It seems likely that a problem with the thymus is part of this troublesome reaction, but again, the underlying mechanisms are still a bit muddy. As the size and effectiveness of the thymus decline with age, it’s no wonder health problems also increase.

We’re finally starting to properly research the thymus and how it works in the hope that we’ll one day be able to treat or even prevent these kinds of diseases. Videregen is one company attempting to lead the way, building on work done in the Francis Crick Institute to identify the progenitor stem cells that underpin the functioning of the thymus and using its own decellularization process to remove the intercellular matrix from tissue and leaving an empty “scaffold” that can be planted with new cells that may allow the thymus to regenerate.

It’s unlikely that the elderly will be the first to benefit if thymus regeneration comes to fruition. Instead, children born with DiGeorge Syndrome, who start life with a thymus that doesn’t work, will likely benefit. Hopefully, it will eventually be available to anyone with thymus problems, although there’s still a long way to go. It will be around three years before clinical trials can start, although Videregen’s other big project, focusing on the respiratory system, is much closer to viability.