If you’ve spent any time studying health and aging, you’ve probably learned to repeat the mantra “mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell.” Their role is incredibly important, and as with so many biological functions, it can decline with age. Understanding better how mitochondria works is the first step to learning how to fix it (https://longevity.technology/news/pitstop-cell-protein-discovery-points-to-healthier-aging/).

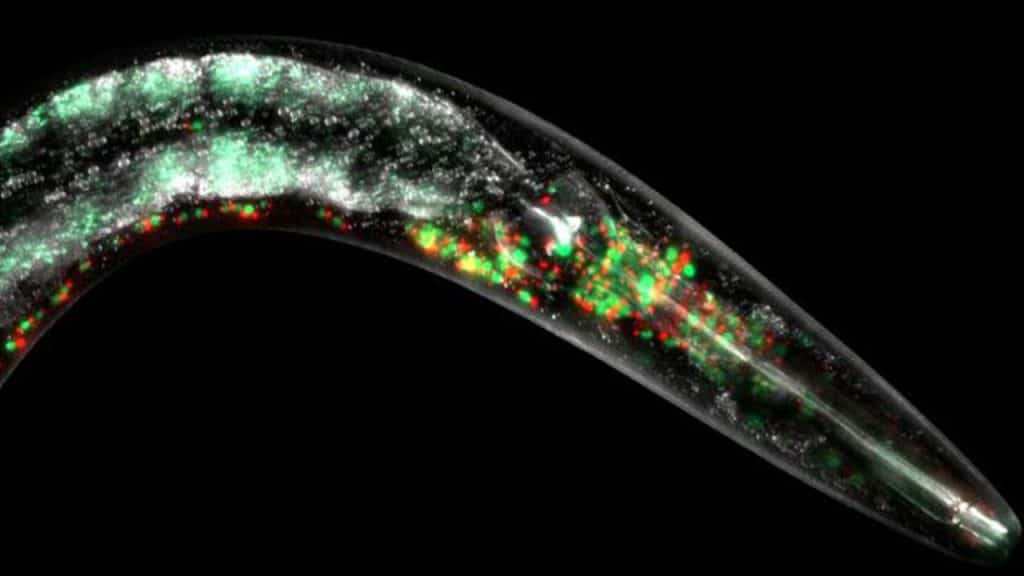

Now, we may have moved a little closer to that goal. Researchers in Australia based at the Queensland Brain Institute at the University of Queensland have been investigating the role a specific protein, known as ATFS-1, has to play in the maintenance of mitochondria. Their study was conducted on roundworms (one of the most popular creatures for this kind of study), but it’s hoped it can also shine a light on human biology.

When mitochondrial function is impeded, energy production and oxidative capacity in our cells are reduced, as is our antioxidant defense. This can happen due to damage or mutation, which tend to occur more and more as we age. Mitochondrial dysfunction then contributes to many of the diseases associated with aging, such as Parkinson’s and dementia.

If our mitochondria isn’t working properly, there are two obvious solutions: fix it or replace it. ATFS-1 is a route to mitochondrial repair. The researchers describe it like a “pitstop” for a racing car. In car racing, sometimes tires get blown or there’s engine trouble, but instead of calling the race over, the driver will pull into the pit lane so their team can give the car some rapid maintenance. This will hopefully be enough to push them over the finish line.

ATFS-1 in roundworms didn’t extend their lifespan. What it did do was improve their quality of life. They remained more agile into their old age instead of losing their mobility. One of the big questions of longevity science is not just how to live longer, but how to make sure we can enjoy our extra years. This study suggests that one way to fend off the diseases, infirmities and pains of aging is to encourage mitochondrial repair.

We’re still a long way from turning this study into a practical therapy, but it does suggest that one day, we may be able to do something to preserve our mitochondria – and therefore our overall health – for longer. Hopefully, this research will become the basis for further study.