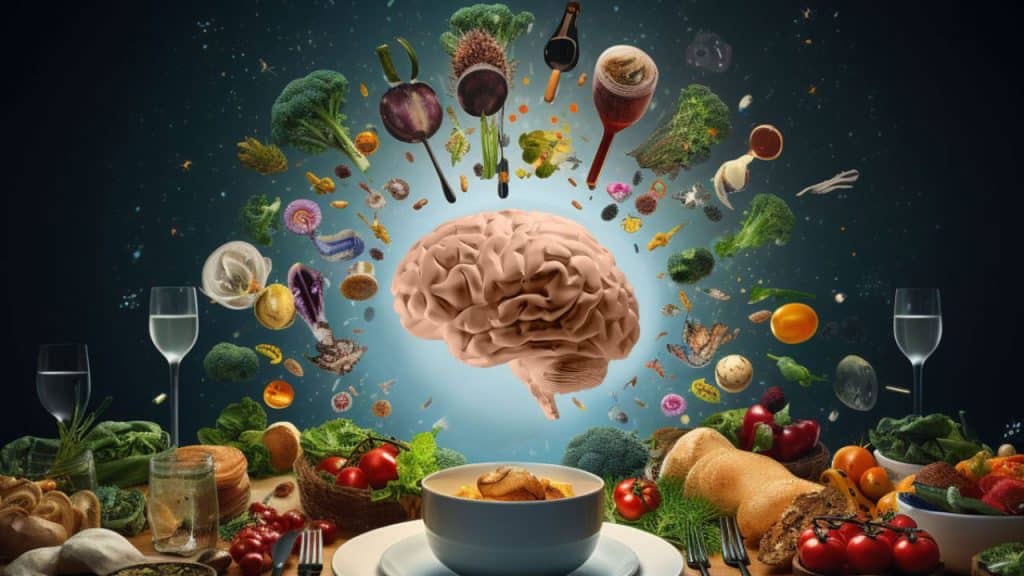

Dietary restriction is typically a tool used to try to lose weight or help the digestive system function better, but increasing attention is being paid to its other potential benefits. It might not be the most obvious approach, but there’s some evidence that dietary restriction may boost your brain (https://longevity.technology/news/buck-institute-researchers-identify-how-dietary-restriction-slows-brain-aging-and-increases-lifespan/).

Growing older impacts every part of the body and mind. Age-related conditions don’t just damage longevity; they erode our quality of life so we can’t enjoy our old age. In the case of the brain, neurodegenerative conditions such as dementia (including Alzheimer’s), Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis can have a devastating impact on memory, mood and concentration, in addition to their physical side effects.

Once neurodegeneration starts, we can’t really reverse it, but there are ways to slow its progress. In this study, conducted by the Buck Institute, researchers found that dietary restriction, such as reducing calories or intermittent fasting, enhanced the performance of a specific gene that has been associated with protecting the brain from the effects of aging, including neurological disease.

It’s difficult to assess how dietary restriction impacts specific genes because there’s still a lot we don’t know about the interplay of different and not always identified factors that cause individuals to respond differently to changes in diet. We all know that some people lose weight easily and some don’t, or that some experience more benefits from certain nutrients than others. We’re not always sure why.

The researchers started with 200 types of flies. Some flies were fed regularly, while others received only 10% of their recommended nutritional content. The two groups had different longevities, and there appeared to be five different genes associated with the variations in response. Of the five, two are also present in humans.

Researchers picked just one gene for the next stage, choosing one that helps cells avoid oxidative damage. Humans without this gene tend to die younger, while mice who had more of this gene had better survival rates.

More testing was needed to explore the mechanisms that allow this gene to work in the way that it does. It seems it impacts certain proteins, known as the retromer, which decides how other proteins and lipids are treated when they end up in your cells.

Essentially, dietary restriction enhances the gene that sorts the proteins that improve brain health and longevity.